by Scott Gleeson

The weavings of artist Juliet Martin merge ancient iconography and textile practices with a contemporary concern for feminist craft and critical engagement with patriarchal society. Trained in the SAORI tradition, Martin works intuitively to create wearable sculptures that play with notions of the male gaze through the lens of the "evil eye," a visual motif especially important in ancient Mediterranean cultures. Martin presents her works in traditional art gallery contexts, calling into question the social dynamics of spectatorship and participation, especially when viewers are invited to don her work. Arrows and eyes draw the viewer's attention to areas of the work corresponding to the location of erogenous zones of the body, making the viewer awkwardly self-aware of their own gender identity and desires. Peripheral Vision speaks to the artist about her training, process, and the motivations driving her work.

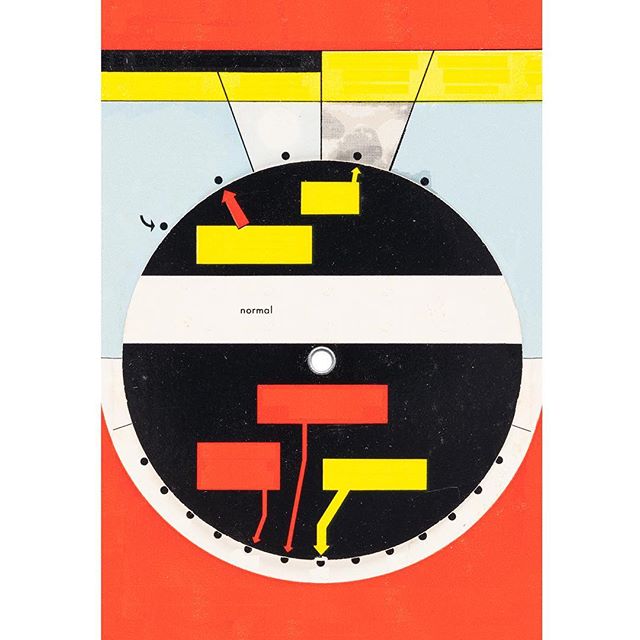

Figure 1: My Eyes Are Down Here: White, Hand-woven and machine-made fabric, embroidery, coat hanger, 53 x 18 inches

Describe a work of art that has been meaningful to you or influential in some way.

I went to see Picasso’s sculpture exhibition at MOMA last fall under protest: he was a jerk, arrogant and sexist. I promised myself I wouldn’t like the work, that I wouldn’t buy the catalog, that I’d just run through the exhibition. To my dismay, his figures were stunning, sophisticated, and simple. He compressed and exaggerated space indescribably. Could I stop being inspired by him? No. “My Eyes Are Down Here” began [Fig. 1].

What is the first work of art you remember experiencing as a child? Was there something about the experience that influenced your practice or decision to become an artist?

Andy Warhol. First I saw “Nine Jackies” in a doctor’s-office magazine. Then I saw him on “The Love Boat.” I didn’t get the joke -- artist as commodity. I was blindly sold on his brand. Almost all of the paintings I did in high school had bright colors, repeated images, high-contrast photos. Everything projected and traced and airbrushed. Even then, the process defined the product for me. Back then I thought nothing was unique, so why bother? So my art looked machine-made. Now I think, if it looks machine-made, why bother.

How old were you when you decided to become an artist? Describe your training and how it has contributed to your current practice.

My mom signed me up for painting when I was four. Everyone was so cool and accomplished and old: third graders! My smock was a Morris the Cat T-shirt that I’d gotten from a Meow-Mix coupon. It was spotless after a few classes, so I took it home and splattered it with paint. But everyone knew what I had done. They laughed and called me the “messy little artist.” It was painful, but I loved painting so much that I kept going and never stopped.

What are the dominant themes in your current body of work and how did your practice evolve to focus on these concerns?

Own the interaction. The decision is mine. When a fruit-stand guy started complimenting me and giving me free fruit for being “cute,” I would take the grapes and run. But a friend said, “Press a dollar in his hand. Stand with strength.” Even though my work is abstract, I keep control. If you look down there, I’ll look back.

Describe your studio practice and working methods? How does this space contribute to your process and development of idea?

I work in an open studio. Sometime children make too much noise. Sometimes adults talk too much. Anyone can inspire.

I don’t like to talk about my projects while in process. It is tricky in a public environment. Once while weaving a uterus and fallopian tubes, I was asked “Is that a hat?” I had protectively woven it upside-down. Sure it’s a hat.

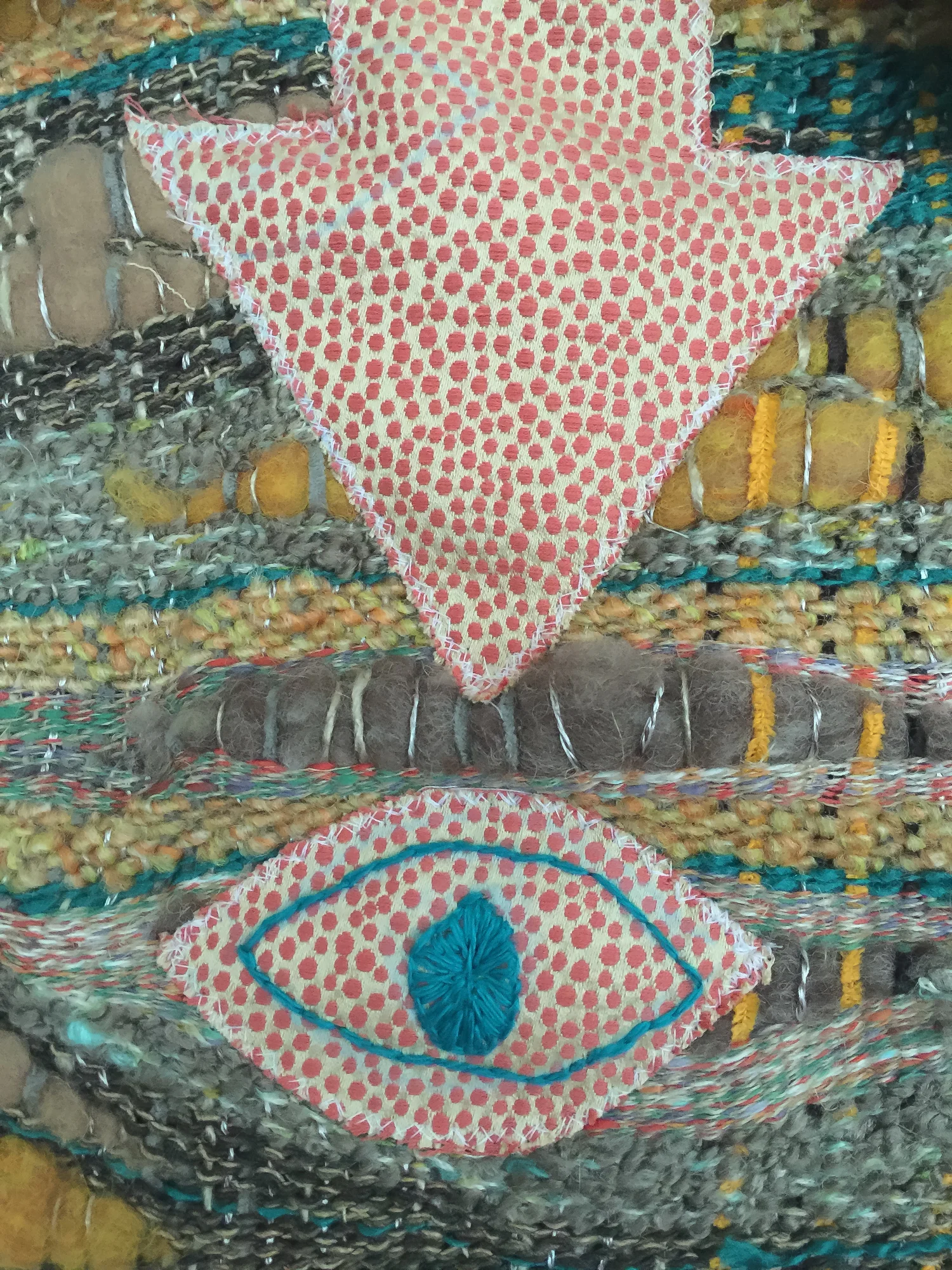

Figure 2: Men I Have Known: Online Romance, Hand-woven fiber, fleece, safety pins, 30 x 20 x 10 inches

How do you make your art? Please describe your materials and techniques and how they developed.

I sculpt fabric: no patterns, no rules. I weave. I cut. I shrink. I unravel. I stain. When I’m afraid of making a mistake, my decisions become timid.

Technique alone does not make my pieces. While they are aesthetically driven, without guiding ideas, the collections would not come together. I want to share something personal and accessible, awkward and delicate, a message with an enjoyable vision. I try reinterpreting goals with each piece.

You have one-way tickets for an all expense paid trip on the time machine! Where would you go and why?

1839, Paris, to the birth of photography. I want to see Louis Daguerre challenge concepts of image making, to watch people introduced to reproduction not with pen or pencil, but with light. I want to see that conceptual firebomb change the way people understand reality.

If you could travel back in time to hang out with a famous artist for a day, who would it be and what would the day be like?

I’d like to have a stich-n-bitch with Louise Bourgeois. I show her how to do a stockinette stitch. She’d show me a garter stitch – of course. We’d bond over mohair being overrated. We’d sing “The Itsy Bitsy Spider.”

Dogs or cats? Beach or mountains? Salt or no salt (it’s a margarita thing)?

My cat likes sitting on my woven fabric -- more product driven than process driven. It’s hard being a female cat in a male-dominated cat world. I’m a Jersey girl – shore all the way. What exit? 63 on the Garden State Parkway. Neither - Guinness on tap.

Describe your work as an educator or administrator and how this relates to you personal art practice.

I taught a two-semester first-year design course. The first half, I asked students to develop one strong concept, research it, and create an in-depth project over the span of the semester. That was a marathon. Second semester was a sprint. Every morning, I presented a new design problem. They had one hour to create a design and map out an interface. The first time, they were horrified: “This has nothing to do with the real world.” It did. Sometimes you have to go with your gut and run with it. Limiting brainstorming time can force me to increase my spontaneity and makes me less self-critical. Blurt first. Censor later.

What kind of music do you listen to? Do you listen to music in the studio?

My name is Juliet and I am addicted to 80’s pop. (“Hi, Juliet!”)

Growing up, I would ridicule CSB-FM 101.1 for playing the oldies. Now they play my prom theme song. I know I have a problem. It is a great day when you hear “The Future’s So Bright (I Have to Wear Shades)” by Timbuk3 and “Jive Talkin’” by the Bee Gees within a 3 hour period. I can stop whenever I want.

Tell us about your current body of work?

I’m weaving memoirs of the untold secrets of my life. Who have I slept with? What are the thoughts in my head? What am I wearing? Now I am asking men to look at me. Not there, down there. My figures, defined by ribs, eyes, fallopian tubes, and arrows, stare back. I’m extracting designs from body parts. Things that were so clear to me are abstract visual riddles. Don’t look at me that way.

What work in your portfolio do you consider your most pivotal accomplishment and why?

“Online Romance” in the “Men I Have Known” collection [Fig. 2]. Once I had made only scarves and jewelry. I wanted to make a piece of non-wearable art. So I wove drapey red fabric with little sparks of yellow and blue. It was pretty, but physically and conceptually flat. Desperate, I showed it to a sculptor. She told me to stuff it. I did. I looked at the new 3-dimensional piece and recognized an ex-boyfriend I’d met online. It was my beginning of expression through sculpture, pushing my weaving beyond the “pretty.”

Figure 3: Plight of the Art Mice, Taxidermy mice, hand-woven fiber, 13 x 10 x 10 inches (one of three boxes)

Talk about a recent exhibition of your art. What pieces did you show and how do they relate to other works in your portfolio?

I created the installation “Plight of the Art Mouse” [Fig. 3] for the Tiny Gallery at the Creative Arts Workshop in New Haven, CT. The Tiny Gallery is a stack of 13” x 10” x 10” plexiglass boxes set in a 15-foot outdoor obelisk. All I was asked was to make something to fit the boxes. I bought taxidermy mice and made expose-style dioramas revealing the mice as abused workers in weaving sweatshops. They told me it was weird and they liked that. They didn’t get it and that was okay.

If I get bored so does my audience.

Tell us about your experience at an artist residency. Where did you go and who did you meet? Would you recommend the residency to others?

I created the handwoven and hand-painted tapestry V is Not for Vagina during an artist residency at Arts Letters & Numbers in upstate New York this spring. Before then, I had become too secure in the textile world, kicking and screaming that fiber is art, too. But when I arrived as a fiber artist among a poet, painters, and a filmmaker, I was forced to put my money where my mouth was. I had to let go of my fiber security blanket.

What is next for you in your art practice?

I am in weaving purgatory. Finished with one collection, I am resolving my next project. I force through anxiety, bad ideas, and wrong turns. I want to curl up in a ball and wait for an epiphany. But new ideas come faster if I keep brainstorming with my loom. I said to my husband, “I’m in between projects, I’m going to be a real bitch.” He’s been there before.

Historically, women have been underrepresented in the commercial and academic art worlds, and where women are represented many are paid less than their male counterparts. How has this dynamic affected your professional career as an artist?

During the Internet boom, I created computer-based art pieces. I made the aesthetic decisions and did the programming myself. I was hailed as a female computer artist -- a woman who worked with numbers was treated as an anomaly. I was looked at as someone who needed to be singled out, given special treatment.

Now, I’ve joined the fiber ladies. Ironically, the mass majority of the textile world is women. Still, I’ve been in shows labeled “female fiber artists,” implying that my gender is as important as the medium.

I don’t know what is better. Maybe I’m just an artist.