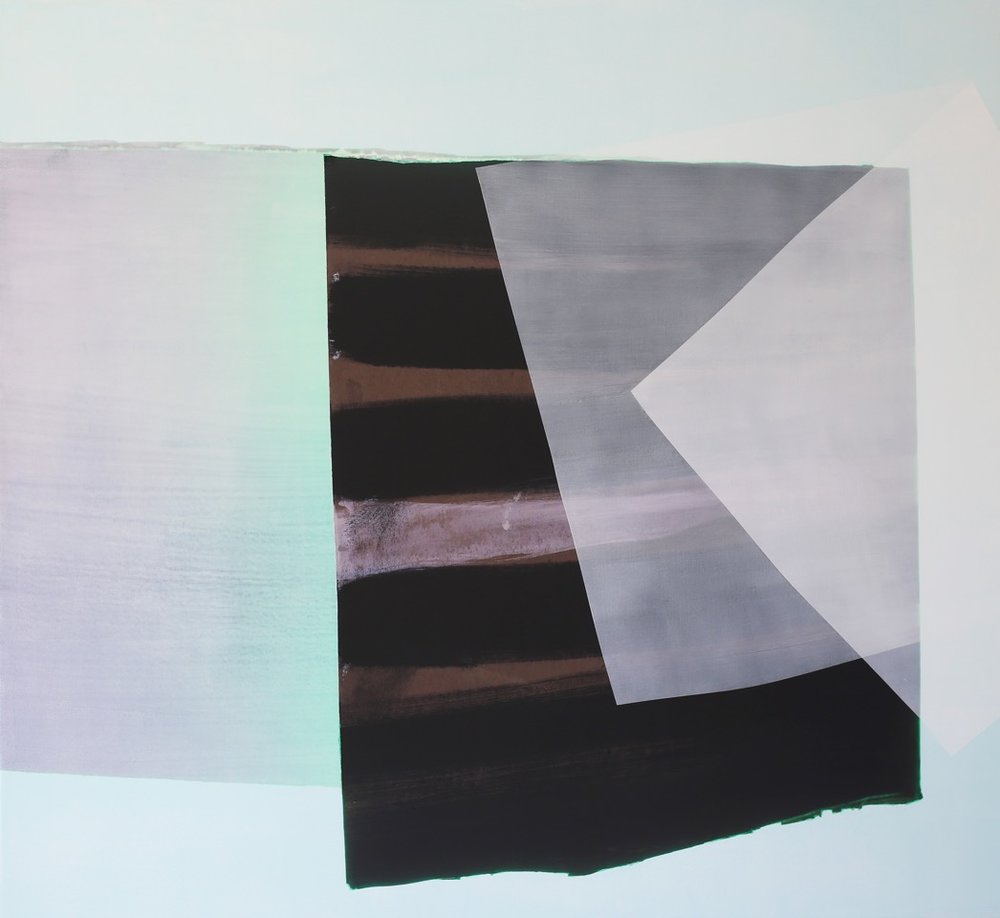

Kate Petley, Untitled Fortune Cookie, Archival ink and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 52 inches

by Scott Gleeson

The nomad distributes himself in a smooth space, he occupies, inhabits, holds that space; that is his territorial principle.[1]

Giles Deleuze & Felix Guattari

The type of painting that is poorly named abstract and which is supposedly brought back to its own proper medium, is implicated in an overall vision of a new human being lodged in new structures, surrounded by different objects. Its flatness is linked to the flatness of pages, posters, and tapestries. It is the flatness of an interface. Moreover, its anti-representative ‘purity’ is inscribed in a context where pure art and decorative art are intertwined, a context that straight away gives it a political signification.[2]

Jacques Rancière

In the light-based era of the digital, the materiality of pigment has come to stand instead for all that the hubris of the virtual disavows – to wit, the laws of time and space, the forces of gravity and accident, and the fixities, limits and constraints of physical form; everything, in sum, that the prevailing powers of our light-based image-world would like to believe they can suspend in the name of a ceaselessly intensifying commercial imperative.[3]

Luke Smythe

Within Adobe Photoshop, the ubiquitous photo editing software, the Merge Down function allows users composing images of multiple independent layers to unify the various strata into a single unified image for the purpose of further editing. The Merge Down function, and the Layers Pallet, generally, operates as a site of rupture in which the artifice of the digital photograph is most fully exposed as a layered abstraction, a sedimentary, stratified territory. Once merged, however, the artifice of the resulting image gives way to an ostensibly natural pictorial space, one the viewer might imagine as the product of a moment in time seen from a single viewpoint. The pictorial spaces of Colorado artist Kate Petley perform a unifying process similar to that of the Photoshop Merge Down function, making them distinctive within discourses of flatness in modern art, a primary focus of which is painting’s interface with diverse graphic media and systems of communication.

Such discourses offer various accounts and configurations of flatness addressing such formal concerns as depth of field and material projection from the surface plane, as well as such semantic considerations as the degree and depth of meaning or psychological force. They also address inherent contradictions within the discourse’s own rhetoric, as for instance, when Leo Steinberg calls Clement Greenberg to account for what he argues is an artificially constructed opposition between the illusionistic pictorial spaces of the Old Masters and the supposedly flat paintings of the Abstract Expressionists and New York School painters. Kate Petley’s work offers an alternative perspective on flatness especially as it relates to the proliferation of light-based images in visual culture, including photography, cinema, and digital culture. The artist’s pictorial spaces equalize digital and handmade image-making processes, overturning persistent media hierarchies by plotting itineraries between genres within a unified, smooth nomadic visual landscape. Petley configures painting not as a singular, media-specific discipline, but rather as a multiplicity of image-making tactics and techniques. Her paintings occupy and hold the genres of collage, digital printing, photography, and gestural abstraction within a territory of pigment-based images, establishing a free flow between them and suggesting the potentiality such points may be abandoned in the future as new techniques or modes of production become available. At stake is the perpetuation of painterly practice as a means of creating resolved abstractions. The mythic status of the mark no longer serves as an index of feeling or psychological expression – it traces creative lines of flight between media, spreading beyond the frame into a vortical non-metric space.

Petley’s spatiality bears its own economy of visual signifiers somewhat different from those of other artists associated with discourse of flatness and light-based images. Many artists whose work operates within these discourses take a deconstructive approach to representation, deploying visual tropes such as the flatbed plane, collage, glitch, blur, pixel, color scale, tonal gradient, gridded drawing pallet, drop shadow, moiré effect, masking, spray, décollage, or the use of fluorescent pigments. The pictorial spaces of Kate Petley look to other signifiers – translucent geometric films, visible brushwork, natural hues, luminosity, modest canvas size, a unified matte paint surface, and atmospheric depth – to communicate notions of unity, balance, harmony, intimacy, and subtlety.

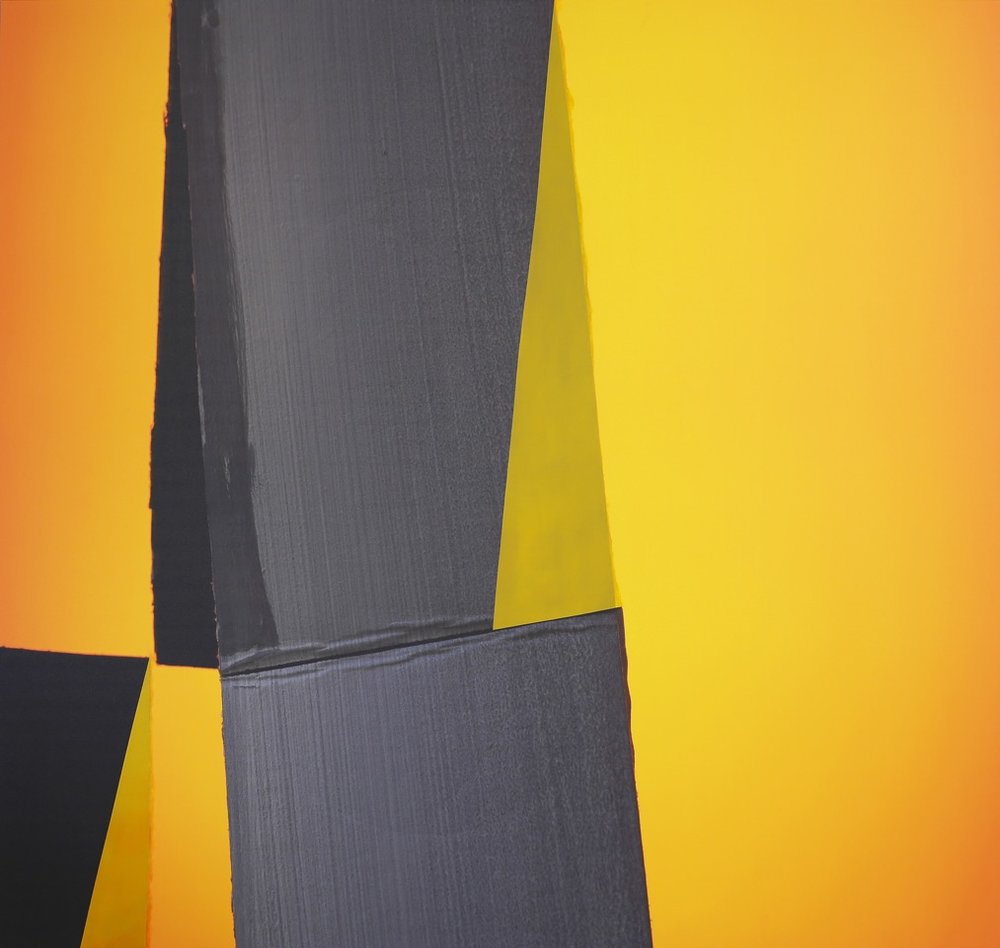

Kate Petley, This Pale Afternoon, Archival ink and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 52 inches

Take, for instance, a moderately sized work typical of the artist’s production, Untitled Fortune Cookie, a pyramidal composition of planar elements set within an atmospheric shallow field. The title calls to mind the popular sculptural confection composed of a thin sheet of cookie dough folded to contain a hidden text. The logical association of the flatness of pages and the transformation of the flattened dough into a three-dimensional form sets the stage for a reading of the image as an allegory of flatness as an interface between spatiotemporal dimensions and media. Executed on a canvas measuring 48 x 52 inches, the image invites viewing from a single spectator standing a few feet from the picture plane, a viewing experience more intimate than much painting associated with Abstract Expressionism or more recent heroically scaled works by such artists as Gerhard Richter, Albert Oehlen, Christopher Wool, or Wade Guyton.

The materials from which the piece is executed, archival ink and acrylic on canvas, further evidence the theme of the interface between print matter and contemporary painting. The image depicts a procession of quadrilaterals beginning with a dark shape in the left of the composition. The shape adds visual weight and contrast, anchoring the composition and serving as a buttress for the orange-hued quadrilateral in the center. Adjoining this shape at its right corner is a translucent, rust-colored form through which we may see another shape set slightly deeper within the arrangement. Already, the artist has established a tension between planarity and depth. The three forms referenced above show little evidence of texture, however, they appear to hover over an orange field of indeterminate depth bearing a slight gradient towards yellow in the center reminiscent of Luminist mountain landscape of the Hudson River School. The underlying quadrilateral partly obscured by the forms above does reveal texture. We see creases, folds, jagged edges and a subtle pattern of corrugation consistent with a digitally printed photograph of a used scrap of cardboard. Out from behind this element lies another corrugated plane emerging from the shadows cast by the forms above.

Once the cardboard scraps begin to assert their material identity (albeit as photographs of the artist’s preliminary collages printed directly upon the primed canvas) we notice that the topmost edge of the central quadrilateral belies its own shallow depth through a scar of exposed interior corrugation. Our discovery is partly delayed in the viewing experience because this plane is divided into two tones, one gray and the other orange. The orange area generally follows the contours of the cardboard, yet where it cuts across the middle plane the brushwork of this thin paint film mimics the jagged edges elsewhere in the composition. Other harmonies exist as well: the same deviation from the clean edge is expressed in the rust film on its left lower side; consistent lighting effects; overall unifying orange tone; and a lateral procession of pointed shapes. The overall impression is one of lateral extension beyond the frame taking place within a shallow space. Yet, what are we to make of the depth expressed within this atmospheric pictorial space, especially as it concerns discourses of flatness as an interface?

Flatness in modern art has come to stand for a range of often-contradictory associations. For Clement Greenberg flatness is configured as a distinctly modernist impulse towards the self-referentiality of the medium of painting in the form of compression of visual depth inversely proportional to an increase in psychological expression of feeling (this included the lateral extension of the image on a large canvas or as series).[4] In response to Greenberg’s theory, Leo Steinberg posited an alternative definition of flatness, termed the flatbed picture plane, in which he traced the genealogy of flatness to the Old Masters’ concern for destabilizing illusionism by reasserting the artifice of the painting-as-window. The pictorial space of the 1950s and 1960s was no longer oriented to the vertical posture of the spectator, but in referencing the flatness of tables across which printed matter is scattered, opened the door for painting that communicates a “different order of experience” – “some garbled conflation of controls system and city-scape, suggesting the ceaseless flow of urban message, stimulus, and impediment.”[5] For Fredric Jameson flatness characterized post-modern art’s tendency towards pastiche and simulation. We may also locate the theme of flatness in Raphael Rubenstein’s analysis of layers within the paintings of Albert Oehlen and Christopher Wool and the way they interface with print media.[6] Jacques Ranciére imagines flatness as an interface, furthering the spatial model of the participant within a landscape – “…new human being lodged in new structures, surrounded by different objects.”[7] Similarly, Luke Smythe’s study of painting in the age of light-based images (photography, screens, projection, and printing) enframes flatness within a context of painting’s nomadic territorialization of other pigment-based media. His definition of new painting is founded upon metaphors of assimilation, fluidity, deterritorialization, and topography.

Smythe’s assertion that contemporary artists have “attempted to broaden their medium’s horizons” by incorporating non-traditional art pigments into their works grafts a relevant new spatial metaphor onto the spatial dimensions already associated with scholarly definitions of flatness – the landscape of the expanding horizon. Certain works in Petley’s oeuvre like Shift, Taken Away, As If I Were Here, Sideways, and Separation bear titles indicative of lateral movement, going from one place to another, as within a sprawling terrain seen from the ground level. What I want to suggest here is that Petley’s pictorial spaces, though retaining certain aesthetic conventions of Steinberg’s flatbed plane, push Smythe’s account of the medium’s territorial expansion to it fullest conclusion by depositing the viewer within the new smooth, heterogeneous, ground-level landscape of the nomad. No longer are we concerned with the sprawling map-like view of a visual field seen from above. The painter and viewer now occupy this territory of expanding horizons in which various image-making media are evenly dispersed, existing as waypoints along a creative trajectory which the artist visits only to leave behind. Petley has dropped the Google Maps avatar into the milieu.

Nomadic space and movement possess characteristics relevant to understanding Petley’s intermedia painting tactics. Philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari outline the key aspects of each in their essay, Nomadology: The War Machine. Firstly, nomadic space is defined in opposition to that of sedentary civilization representative of an authority which occupies a delimited, measured, parcel of land. Endemic to sedentary space are homogenization, the sedimentary accumulations of history and power hierarchies (configured as layers or striations), metrics, rootedness, boundaries, movement along predetermined pathways from point to point, and an impulse toward territorialization. Conversely, nomadic space eliminates such power hierarchies, boundaries, and metrics, rejecting the bird’s eye view of the map in favor of the free, haptic, vortical, flowing, temporary occupation of open space. This model “consists in being distributed by turbulence across a smooth space, in producing a movement that holds space and simultaneously affects all of its points, instead of being held by space in a local movement from one specified point to another.”[8] The potential of nomadic space as a model for recent trends in contemporary abstract painting is prefigured in Leo Steinberg’s model of the flatbed plane: “any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which information may be received, printed, impressed.”[9] Furthermore, Rancière suggests that this new space of flatness constitutes a milieu capable of being inhabited: “…a new human being lodged in new structures, surrounded by different objects.”[10] If we imagine Petley’s dominant media - photography, collage, and painting – as “different objects” and her canvases as a “receptor surface” on which these objects are scattered then, painting in this paradigm may be interpreted not as an analog to the flows of information culture or urban life, but rather a model of practice, an itinerary, for negotiating contemporary visual culture.

Kate Petley, One Day, Archival ink and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 76 inches

A logical conclusion of Petley’s nomadic model of painting is that it attempts to occupy and hold the virtual spaces of the digital realm (and Delueze’s model of nomadology has been relevant to recent media theory); however, the visual evidence does not support this. Paintings such as One Day and This Pale Afternoon possess luminosity consistent with the naturalism of landscape painting and photography, resisting the aforementioned tropes of works inspired by or which successfully circulate on digital platforms. Evidence of pixilation, glitches, rainbow color scales, and the perfection of digital design are nowhere to be found. Instead the artist presents pictorial spaces suggestive of a sunset at dusk or a misty, cold day along the Front Range of Colorado, a place where rolling plains abut the Rocky Mountains, the artist’s home turf. The subtlety of the painting’s lighting effects is complimented by an equally nuanced representation of brushwork. Petley’s brushwork forms translucent skeins or opaque passages carefully nested within printed areas. Within the printed passages themselves, Petley preserves brushwork on individual collage elements – scraps of cardboard, paper, and acrylic transparencies. In One Day, the hand-rendered effects of the triangular sections of brushwork reveal their identity as paint, yet an equivalence is established with the printed brushwork on the folded cardboard collage element, whose diagonal fold in the center of the composition acts as a foil to the perfectionism of the digital. Petley is careful to mix her paints to match the local color, modifying only the value, thus enhancing the shadow effect and therefore the spatial depth of the image. Petley’s titles further secure a reading of her nomadic pictorial spaces as habitable domains by introducing a temporal dimension into the spatial model already established, such that One Day and This Pale Afternoon might be as easily located on a calendar as dated paintings by Picasso or On Kawara.

Thus, what Smythe identifies as the “hubris of the virtual,” with its disavowal of time, space, and gravity, constitute a force against which the pictorial spaces of Kate Petley resist. They do not incorporate digital processes in order to circulate on screen. Nor do they revel in the materiality of pigment for the sake of proclaiming the status of painting as an object. Rather they embrace the heterogeneity of contemporary image-making by merging the formerly stratified “layers” of media-specific practice, temporarily occupying the painting-on-canvas format as a waypoint along a trajectory which might just as easily be left behind.

[1] Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Nomadology: The War Machine, trans. Brian Massumi (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986), 51.

[2] Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics (New York: Continuum, 2004), 16.

[3] Luke Smythe, “Pigment vs. Pixel: Painting in an Era of Light-Based Images,” Art Journal (Winter, 2012): 118.

[4] David Joselit, “Notes on Surface: towards a genealogy of flatness,” Art History Vol. 23 No. 1 (2000): 20-22.

[5] Leo Steinberg, "Reflections on the State of Criticism," Artforum (March 1972): 47-48.

[6] Discussing apparent erasures within Wool’s brushy monumental abstractions he writes, “What we get instead are paradoxical pictures in which the artist seems to have obliterated a painting-in-progress and then presented this sum of erasures as the finished work. But has anything actually been covered up? Is there something under Wool’s erasures?” Raphael Rubenstein, "Provisional Painting," Art In America (May 2009): 126.

[7] Rancière, Politics, 16.

[8] Deleuze, Nomadology, 21.

[9] Steinberg, "Reflections," 46.

[10] Rancière, Politics, 16.