Devra Freelander, Mineral Analog (Pink / Charcoal), Fluorescent acrylic, plaster; 10 x 12 x 4 inches; 2016. Photo credit: Peter Nicholson

by Scott Gleeson

For artist Devra Freelander the Arctic landscape is a site where divisions between the real and virtual, natural and synthetic are subsumed by the mediating influences of historical, aesthetic, political, and scientific discourses. Like artists before her, Freelander is compelled by the optical qualities of light's effect on ice, which though solid remains dynamic in its response to the conditions of the environment through modification of its forms and crystalline structure. Artists such as Frederic Edwin Church in his painting The Icebergs (1861) similarly revered Arctic ice for its dynamic chromatic potential and the to degree to which it could become a screen for the projection of ideology underpinning Luminist landscape painting of the 19th century. More recently, Roni Horn has devoted much of her attention to replicating ice's optical effects in an ongoing series of cast glass sculptures, which seem to privilege an interest in human perception and embodiment over ideological or political concerns. Yet, whereas Freelander may share an interest with her predecessors in the visual properties of ice, her art is informed by an additional array of concerns ranging from the digital aesthetics of screen culture to contemporary climatology. Works like Mineral Analog (Pink / Charcoal) evince urgency about the profound changes to human behavior needed to mitigate the deleterious effects of global climate change on the planet's polar ice. However, rather than advocating a political message or attempting to raise awareness, as a 2015 public project by Olafur Eliasson, Ice Watch Paris, endeavored to do, Freelander's sculpture remains ambiguous, operating within what art historian W. J. T. Mitchell, author of Landscape and Power, might call "a semiotic and hermeneutic approach that treat[s] landscape as an allegory of psychological or ideological themes." Amidst the specter of rapidly disappearing and threatened landscapes, Freelander offers up synthetic analogs that play upon consumerist desires by situating the idealized, timelessness of the virtual within the context of geological time.

Peripheral Vision discusses with the artist the motivations driving her artistic production, her profoundly physical creative process, and the early recognition she has achieved for her work.

Tell us about a museum exhibition or travel experience that has influenced your practice in a significant way.

In 2014, I traveled to Antarctica on a National Geographic-sponsored expedition. I spent two weeks sailing around the Antarctic Peninsula at the height of the southern summer season, when the sun spends hours dancing on the horizon, never quite dipping below, dusk and dawn lasting for hours on end. The image of that too-large fluorescent orb remaining tangental to our planetary topography for so unusually long has haunted me ever since, and has become the starting point for several series of my work. The entire Antarctic landscape resonated deeply within me on an aesthetic/perceptual level, and I found myself experiencing the southern continent in distinctly digital terms, surprisingly enough. The pristine untouched snowscape was ideologically reminiscent of a clean desktop screen, and the sun’s ultraconcentrated UV rays bouncing off of stark blue-white ice produced a retinal burn akin to the feeling of staring at your phone screen for too long in the dark. Of course, when discussing Antarctica, it is impossible to avoid the conversation of its own inevitable demise due to climate change. Antarctica is an empathic reflector for our planet, absorbing the weight of our species’ carbon emissions as it slowly calves under its own icy weight. The collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet will raise global sea levels dramatically, affecting every coastal city and habitat across the globe. Despite Antarctica’s physical and psychological distance from society, it is a massively affective force in our lives. Since visiting, my work has been inextricably influenced by the complicated emotional landscape of this inimitable and spectacular place, and I hope to return again soon.

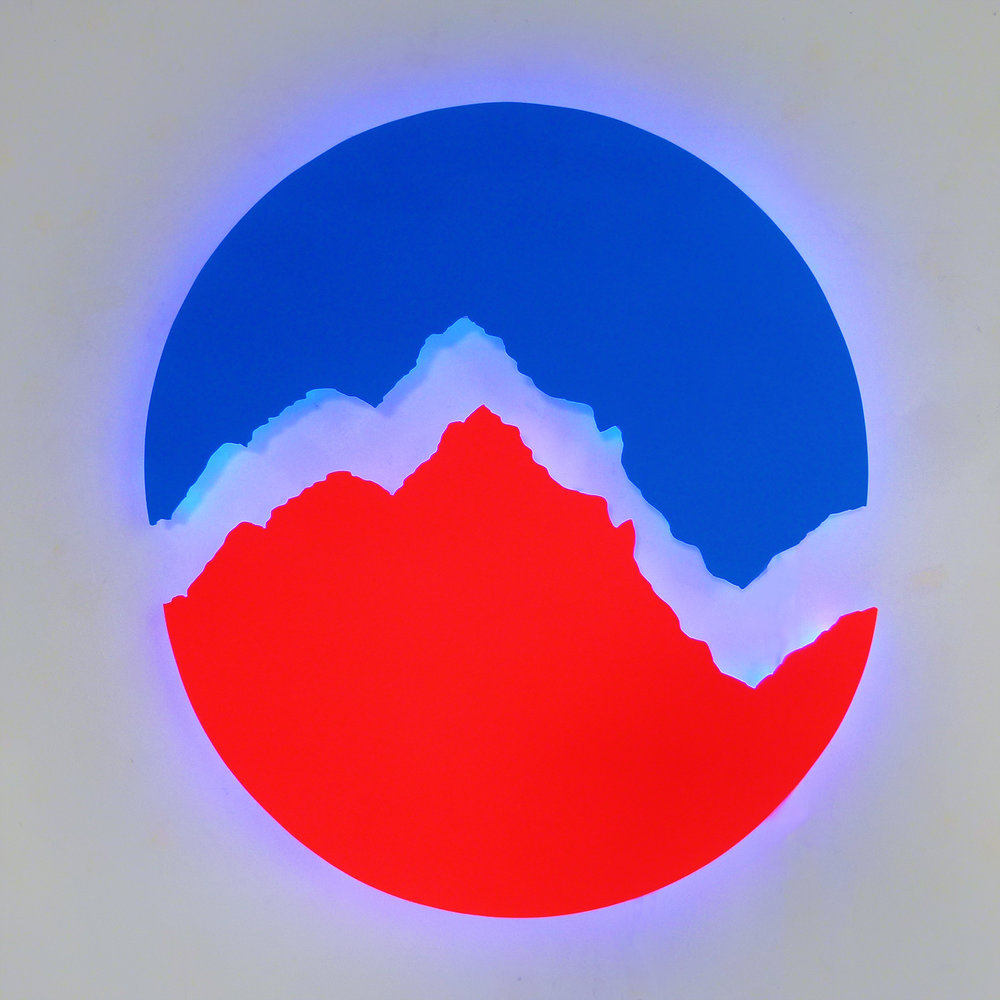

Devra Freelander, Cola Mimesis, Steel, LEDs; 24 x 24 x 1/16 inch; 2015. Photo courtesy of the artist.

What are the dominant themes in your current body of work and how did your practice evolve to focus on these concerns?

My sculptures are formed around themes of climate change, geology, digital aesthetics, and the sublime. Polarity resonates throughout my work: I am obsessed with objects and ideas that occupy both ends of any spectrum simultaneously, or the feeling of being at-odds with yourself. I apply contemporary tropes sourced from digital design softwares, like gradients, emoticons, and fluorescent colors, to ancient and reverent geologic forms like mountains and glaciers, in an attempt to reconcile the disparate time scales of the two. This interest began for me as a child: growing up in the 90s, much of my creative development occurred on the computer, and thus my sense of spatial aesthetics was deeply informed by screen-based two dimensionality. I have also always been obsessed with rocks, perhaps as a counterpoint to this adolescent digital immersion: while the internet is instantaneous and intangible, rocks are slow and reliable. I’ve collected rocks since my childhood, and view them as phenomenologically grounding (and deeply powerful) objects, despite their perceived banality. Some of my earliest works were zen garden-inspired rock, sand and mirror installations that were organized according to design principles like the phi grid, and I’m currently working on a video where an anonymous user controls the sunset through scrolling on an iPod classic carved out of orange alabaster. My practice is an ever-evolving exploration of the relationship between the digital and geologic realms, and I am still fascinated by every brief moment of synchronicity between the two.

How do you make your art? Please describe your materials and techniques and how they developed.

My studio process is intensely physical: I create silicon and concrete molds of objects that I then cast fluorescent-pigmented epoxy resin and plaster into. I love using epoxy resin for its durability and ability to both transmit and retain fantastically colored light. Plaster, on the other hand, is inherently geologic: it is pulverized gypsum, domesticated to supplant the industrial sphere. The material history of plaster, concrete, and other geologically-mined casting substrates is fascinating to me. Once I’ve finished casting these materials into their molds, I spend hours intensely sanding the resultant sculptures in order to bring their surfaces to a mirror-like finish. I used to spray-paint my sculptures with fluorescent enamel, but I have since switched to mixing fluorescent pigments directly into the material itself, as opposed to applying a surface layer of color; this way, the color is integral to the object itself, and the depth of any color is directly tied to the thickness of the material it is embedded in. This process lends itself to obsessive sanding quite well, as the longer I sand something, the more vibrant it becomes. At its base level, sanding is touching. I love the idea of repeatedly rubbing an object with my hands in order to reveal its inner perfection; there is an undeniable intimacy to that action. A few days of sanding will render any object beautiful, in my eyes. Despite my obvious interest in finish fetish and well-defined minimalist objects, I love to include small moments where my hand is visible in the work, like slight wobbles in the surface sheen that subconsciously contradict the impeccable crispness of the overall form. In striving for digital perfection, my hand leaves inevitable traces that impart the warmth of human error. While the fabrication of my sculptures is highly physically involved, they always begin as digital renderings on my computer. I model the forms in Rhino, isolating and vectorizing geologic elements from photographs I’ve taken in the field, and experiment with colors options in Photoshop. In this way my work is equally influenced by digital and physical modes of production, oscillating between the two from inception to completion.

Dogs or cats? Beach or mountains? Urban or rural? Salt or no salt (it’s a margarita thing)?

Dogs and cats; mountains on the beach; rural escape punctuated by urban involvement, and always (always) salt!

Tell us about your experience at an artist residency. Where did you go and who did you meet? Would you recommend the residency to others?

I spent this past year participating in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council's Workspace Residency, which is an amazing 9-month program that gives free studio space to visual and performing artists/writers in New York City. The studios were located in the financial district of Manhattan, right off of Wall Street, which was definitely not a typical place for an artist's studio. Making art in this environment, especially large-scale sculpture, was hilarious, difficult, and vastly rewarding. My last studio prior to LMCC was in an industrial warehouse in Rhode Island, where there were six Home Depot's within a five-minute radius and I could drive and park at the loading dock every day. Getting 50 lb bags of plaster to a studio on the 24th floor of a Wall Street office building was definitely more belabored, to say the least, and forced me to plan each sculptural endeavor more thoroughly than I might have previously. I also stuck out like a sore thumb when I'm covered in plaster waiting for the gilded marble elevator next to a group of stern men and women in crisp suits, but I think there has been a definite positive impact on my work from creatively functioning in/against this corporate context. The absurdity of the studio's location also lent itself to an undeniable intimacy amongst the participants in the program: our studios were a hidden artistic oasis at the belly of the corporate beast, a wildly safe space for experimentation tucked away amongst fluorescent-lit offices and cubicle ghost-marks. I've met some of the most incredible artists through this program, and was consistently impressed by the caliber of work being produced in that beautiful, bizarre space. I'm incredibly grateful for the opportunity, and can't speak highly enough of LMCC and their residency programs.

Describe a grant or award you have received that has contributed to the development of your practice?

I received the RISD Graduate Studies Grant while I was in the first year of my MFA program there, which was the first grant or award that I had ever received. I had always dreamed of traveling to Iceland, which is one of the most geologically sublime landscapes on the planet, but I never had the financial ability to make it happen. Serendipitously, one week before I found out I had received the RISD grant, I learnt that I had been accepted into a month-long residency at the Fjuk Arts Centre in Northeastern Iceland. The stars aligned, and I was able to use RISD's grant money to travel to Iceland for a month that summer, developing a new body of work that engaged with Iceland's glaciers from a digital and experiential perspective. My time in Iceland was formative not only because of the momentous and inspiring landscape, but also because of the challenges of making work in a rural international studio so far from home. I knew I couldn't afford to ship sculptures back from Iceland, so instead of sticking to my familiar mediums I bought a camera and began to experiment with video for the first time. I filmed a screen-captured performance of myself "erasing" Iceland's largest glacier, Vatnajokull, one pixel at a time in Photoshop (https://vimeo.com/148544390); this piece then led to another screen-captured performance video, 'Touching Antarctica', in which I caress (and implicitly melt) the outlines of icebergs in Antarctica (https://vimeo.com/169102270). I had never worked with video previously, and likely never would have if I hadn't been forced via the circumstances. My time in Iceland was life changing on many different levels, and I'm deeply grateful to the RISD Graduate Studies Grant for allowing it to happen, and for giving me the confidence and skillset to apply to future grants. This October, with the help of the St. Botolph Club Foundation's Emerging Artist Award, I will be traveling to the Arctic Circle for a month to work on the next iteration of these screen-captured polar performance videos.

Devra Freelander, Polar Desire 01-03 (Installation View, RISD MFA Thesis Exhibition); Fluorescent Acrylic, Plaster, Epoxy Resin, Marble, iPad, Digital Video (https://vimeo.com/169102270), Polar Seltzer can; 12 x 5.5 x 10 feet; 2016. Photo credit: Peter Nicholson

What is next for you in your art practice?

I'm interested in scaling up my work, and creating outdoor sculptures that engages directly with the landscape rather than pantomiming that relationship from within a gallery. This summer I will create my first outdoor public sculpture at Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, NY, through their Emerging Artist Fellowship. Inspired by my time spent under the midnight sun in Antarctica and Iceland, I will insert a life-size fluorescent gradient disc directly into the landscape, functioning as a perpetual sunrise (or sunset, depending on your personal ecological perspective). My work has always been inspired by ancient natural environments, and so I'm curious to see what would happen when I place the sculptures in the actual environments that inspired their creation. Of course, large-scale outdoor sculpture is rather financially prohibitive, so in the meantime I have been experimenting with digital video as a perspectival surrogate for direct environmental immersion. I will also be traveling to the Arctic Circle next October with the Arctic Circle Residency, during which time I plan on gathering massive amounts of digital data on the threatened polar landscape. I have hundreds of ideas for what I want to do while there, but at the very least I plan on 3D scanning icebergs in order to create fluorescent resin sculptures based on that data, as well as film a performance involving some personal haptic interaction with icebergs. I have also began a few exciting collaborative projects this year; I co-founded MATERIAL GIRLS (http://materialgirls.work), a collective of young female-identifying sculptors whose work engages with the materiality of contemporary femininity. We had our first exhibit this past May at SPRING/BREAK BKLYN Immersive, and are working on a new collaborative installation called NO NEW FORMS that will open at Trestle Projects in Gowanus, Brooklyn later this month. I'm excited to champion the work of my peers, especially in such a historically male-dominated field; MATERIAL GIRLS is an ever-expanding platform for uninhibited bad-ass women who know how to use power tools and aren't afraid to brag about it.