Squeezing Sorrow from an Orange (Installation view), Orange peels, scent, radiator, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2017.

by Helen Lewandowski

Spanning performance, installation, sculpture, and audiovisual work, Cathy Hsiao is a master of translation—from exterior to interior, the natural world to industrial manufacturing, dense concrete urbanism to the emptiness of a desert plain, her work sublimely plays at the edge of the awkward and often elusive translation between spaces and mediums. Infused with semiotics, Hsiao explores in her work Ferdinand de Saussure’s idea of the ‘sign’, with its ‘signifier’ (sound) removed from its ‘signified’ (meaning). The noises associated with words are liberated into beautiful, abstract, and often melancholic meditations on memory, tradition, and ritual. Originally from a background in craft and organic materials, Hsiao has since integrated industrial processes and repurposed everyday materials—filling the skins of bananas and avocados with magenta concrete. This highlights another key theme in her work, the natural versus the urban, and as one learns about her upbringing the origins of her aesthetic becomes legible.

Growing up in Taiwan, Hsiao spent her childhood raised in a quiet household surrounded by concrete towers and a canopy of the dense noise of city life. Drawing upon this background, Hsiao layers the sounds of city life with industrial materials in her works. Hsiao also, however, expresses in her work a yearning for the city’s opposite, the desert: “[It] was always something I craved, it was a horizontal infinity of space and sound, my home interior materialized while also contrasting with the density and noise of the vertical infinity that shaped my outside environment.”[1] Though now based in Chicago, Hsiao continues to seek the desert with residencies and trips to Joshua Tree National Park in California. The sparse, silent and barren landscape takes on particular meaning in Hsiao’s work: “I’d like to think there are traces of the desert in everybody’s practice. It’s that place that seems alien and uncanny in its beauty—speaking a completely foreign language to the one we know but still, somehow, resonating an intuitive sound in us that we recognize as part of our own.”[2]

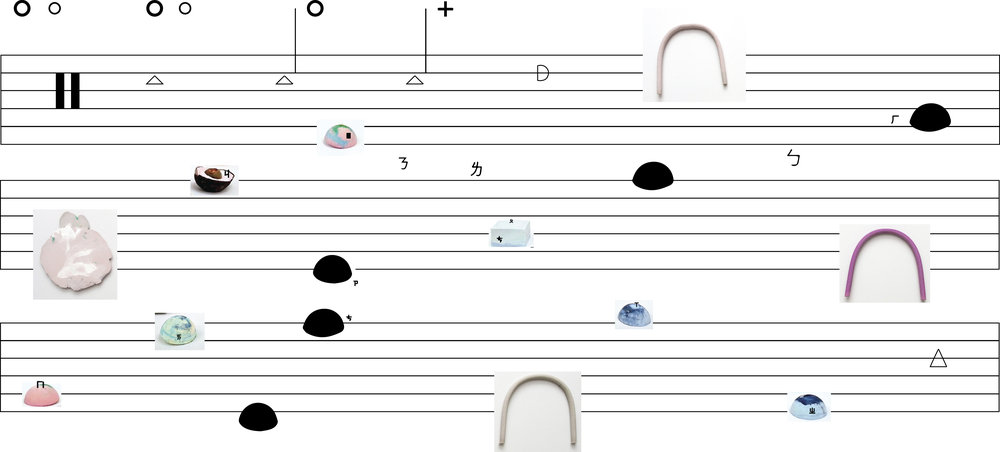

Cathy Hsiao, Bopomofo Score Key (Songbook for Sculpture), studio view, Concrete, recycled textile dyes, Dimensions variable, 2017

Bopomofo Songbook for Sculpture (2017 – ongoing) quite literally takes translation as its subject: bopomofo refers to a system of transliteration of Taiwanese Mandarin into phonetic characters. The word bopomofo itself is a colloquial term formed from the first 4 of the 37 characters of the alphabet. As a child, Hsiao was taught her native tongue by her mother using this system of sound-symbols. For Bopomofo Songbook for Sculpture, the language is transformed into “a concrete poetry that mobilizes sculpture as a literal language”. The ‘key’ from the songbook ascribes different sculptural elements such as a concrete-filled avocado shell, a pink arch, and a stone-like turquoise dome - each with the Zhuyin (bopomofo) characters. The vocabulary is further extended from sculpture to score.

Bopomofo, Page 1, Score 1 (Songbook for Sculpture), studio view, Concrete, recycled textile dyes, acrylic paint, accompanying sound performance, 6 x 4 feet, 2017

The sculptures stand-in for notes on a classical music staff, complete with a neutral clef, typically used for pitchless percussion instruments. The curved domes and arches echo the shapes of musical notation: semibreves, rests, and slurs. Hsiao then arranges these cast forms as a spatial text or musical score. The artist declares, "The vocabulary comes from spaces in my environment abstracted from their context: a puddle of rain, a concrete sidewalk square or its crack.”[3] Such experimental graphic notation at its core has origins in the work of composer John Cage (1912-1992), who pushed the limits Western classical music notation. In his famous Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1958), for instance, he drew shapes on top of the staff to give the musicians a range of notes rather than specific direction, forming a collaboration between concept and performance with ever-changing possibilities. In terms of what we can expect for the future of this work, she envisions the songbook as an entire cycle of audio compositions based on sculptural casts. For her, the inspiration of this project springs from a “desire to objectify and make tangible”.[4]

Songbook for Sculpture (detail)

In Hsiao’s sprawling sample soundscape Density (2016-17), one can see not only the influence of John Cage but also that of musique concrète. Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) led this movement in the belief that while traditional music turned abstraction (written music) into audible sound, it would be possible to take real sound recordings and abstract these into compositions. In Schaeffer’s words, “Sound is the vocabulary of nature...noises are as well articulated as the words in a dictionary. Opposing the world of sound is the world of music.”[5] His argument sits well with the prominent themes of Hsiao’s work: nature, language and translation. The artist’s own thoughts on Density enlighten us to the subtle links between her sound and sculptural works - the sedimentary - “If we linger to listen, gradually layers of sound can compress into one. Some call this static. I call it sedimentary, and the sediments of sound solidify with my own heartbeat.”[6] Concrete, which forms or inspires many of Hsiao’s pieces, is essentially an artificial sedimentary rock, coarse aggregate mixed with fluid cement. Density’s soundscape matches this description perfectly; the ethereal electronica and hip-hop slowed down by 900-1000% out of recognition is the cement, interspersed with hard aggregate of percussive sleet on roofs, heartbeats and the beating of moths’ wings. By combining them together, Hsiao orchestrates harmony and rhythm from everyday sounds that we often take for granted. As Cage wrote in his 1937 manifesto:

“Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating. The sound of a truck at fifty miles per hour. Static between the stations. Rain. We want to capture and control these sounds, to use them not as sound effects but as musical instruments.”[7]

Density, Sound (field recordings, samples, voice, guitar, drum machine), 00:12:42, 2017

Performance as part of experimental video documentation: http://www.plantandanimalstudio.info/sound/

In Squeezing Sorrow From an Orange, performed in 2016 at the McLean County Arts Center, Bloomington, Illinois, Hsiao kneels on a small mat with an electric guitar, a ripe orange in hand. Hsiao begins with a long, low strum, using the fruit as a makeshift pick. Over the course of a few moments, the atmospheric riffs heighten, and the orange peel gradually gives way. First a zest, the fragrance of the orange fills the room, inaudibly interfering with the noise. Finally, though, the juiced orange gives way, sliced away—the chords halt and gasp and stutter back to life, then are silenced. Even without the knowledge that the piece uses a blues progression, the slow, purposeful sounds resemble a lament—and it is a lament to “mourn the loss of language.”[8] The orange takes new meaning as the first word Hsiao learned in English—since then, English has become more dominant, more readily-used than Hsiao’s native Mandarin. Squeezing Sorrow From an Orange reflects this with the gradual destruction of the orange. Because of this, Hsiao has no set time for the piece; it is entirely dependent on when the orange ‘pick’ is destroyed and sounds dissipate into pulp, “a simple exercise in amplifying the sound of an object that has no socially recognized language”.[9] Her piece is minimalist yet infused with palpable emotion and meaning—mirroring the disintegration of language and the loss of memory.

Such an organic, time-based, absurdist and, above all, meditative performance has strong connections with the 1960s Fluxus group’s practice, whose famous ‘Happenings’ often incorporated improvisation, collaboration, and installation through a durational artwork within an art space. Works like Make a Salad (1962) by Alison Knowles (b.1933), for example, involved performing daily rituals (the titular salad making) in the gallery to live music. Hsiao channels the Fluxus group’s priority on the performance itself. To her, “Process is usually something that supersedes product for me, especially in terms of improvisation both in language, sound and sculpture.”[10] This is further shown by the orange peel which is placed on radiators to create aromas in the space, smell of course being near-impossible to document. Again, however, Hsiao’s work has strong conceptual links with Cage, a key influence to the Fluxus movement who modified instruments to add elements of chance to his pieces. Although items were attached to particular parts of the piano for Cage’s prepared piano pieces, first developed around 1940, these would often become dislodged at entirely random intervals. Similarly, who knows how long Hsiao's orange may last or affect the sound of her guitar?

Program for Plants by Cathy Hsiao and Mikolaj Szatko from the one-night performance, The Plant Sessions Abuse of Vegetational Concepts, December 12, 2015, SUGS Gallery, The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, Curated by Brian M. John as part of the Mercury exhibition curated by Brian M. John and Linda Tegg. soundcloud.com/cathyhsiao

Program for Plants (2016) also focuses on the organic; it is not humans, but plants, who are the intended audience. As Hsiao states, it is “Conceived to be at frequencies which plants are theorized by some to be better able to perceive”.[11] The ambient soundscape consisting of kalimba, electric guitar and voice looped through a mixer certainly evokes images of serene nature. One can imagine perhaps supersonic or subsonic frequencies lost on us, but absorbed by the foliage. In the performance, Hsiao and collaborator Mikolaj Szatko are surrounded by grasses and bathed in neon light, transforming the studio space into something of a greenhouse. The artist’s urban Buddhist upbringing is brought to life here. Communicating to plants brings to mind the idea of dependent origination or Pratītyasamutpāda - that everything is connected, rather than humans and plants being entirely separate entities. However this clinical studio space is a far cry from the Buddha’s forest; Cathy Hsiao is an inhabitant of the concrete world and she is connecting with the nature as best she can, through sound. Again, she challenges the limits of communication and language, asking us to ponder “are the plants listening?” Language becomes an impermeable screen, the powerful desire for communication is at odds with the impossibility of translation to an alien entity.

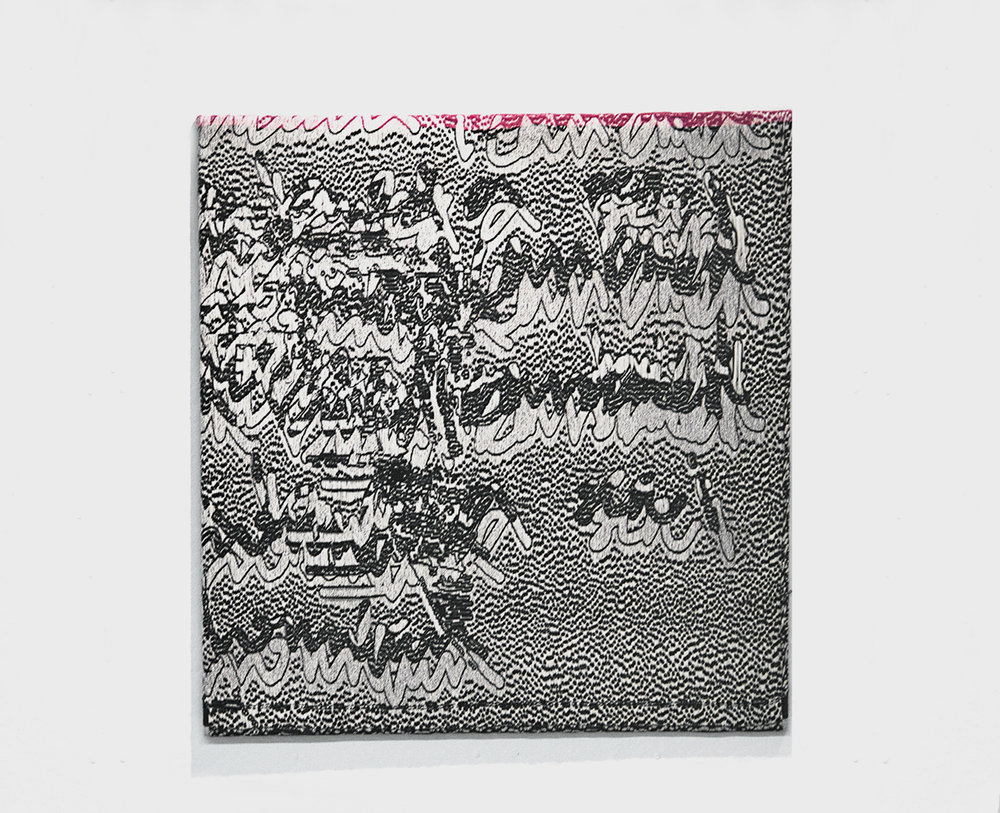

The ‘sedimentary’ layering of sound in Density is further explored by Hsiao in her Screen Weaves. Striking black-and-white woven patterns resembling static interspersed with arch motifs repeated from Bopomofo Songbook for Sculpture, the Screen Weaves have visual parallels with the Abstract Expressionist photography by Aaron Siskind (1903-1991) from the late 1940s to 1960s—close-ups of graffiti, ripped posters, and peeling paint that isolates the surface from its context in a decorative and sublimely beautiful way. Like Siskind (who spent several years in Chicago), Hsiao finds an aesthetic delight in the “visual geography” of graffiti; some of these Screen Weaves draw upon taggings found near her home in Pilsen, a neighborhood on the Lower West Side of Chicago.[12] Hsiao’s abstract compositions again take sounds as their starting point, however, by isolating and distorting everyday audio on the street. After collecting noise data from the environment, she processes this into a digital file that a jacquard loom can read. Though the loom is programmed to lift pedals in a pattern corresponding to the data, the artist still has to hand weave the pattern, a process which combines industrial production with the intimacy of the hand of the artist. Distorted ‘noise’ from the streets and urban decay is translated into an interior, decorative environment with soft textiles. For Hsiao, “The weave draft is extremely similar to a graphic score visually, so I‘m interested in subjectively moving between these two systems and having a structure that can potentially be a draft and a score, simultaneously weavable and playable and amplifying that structure-as-translation.”[13] This exemplifies Hsiao’s ability to permeate themes across her work without medium restricting her in any way.

Permutations (Screen Weaves series)

From the static and graffiti patterns hand-woven into the compositions of Screen Weaves to the aleatoric durational performances like Squeezing Sorrow from an Orange, Hsiao’s work invites the viewer to re-encounter the oddly familiar, the uncanny ‘desert’ in a completely new context. The artist creates new language by stripping sounds of their signifieds and systems of meaning, thus endowing a heartbeat or sounds of the natural and urban landscapes with equal stature. This language, like the best of Cage’s and Schaeffer’s compositions, draws upon the beautiful chaos organic in the everyday. The familiarity of its symbols resonates with primordial meditation on memory—a universality which extends far beyond the autobiographical.

[1] Gordon, Lydia, “Interview with MFA Artist Cathy Hsiao”, 2016. http://sites.saic.edu/mfa2016/interview-with-mfa-artist-cathy-hsiao/

[2] Ibid.

[3] Hsiao, Cathy. Artist’s Statement. http://www.plantandanimalstudio.info/bio/

[4] Email from the artist, Cathy Hsiao, 2017.

[5] Hodgkinson, Tim, “An Interview with Pierre Schaeffer”, Originally published in 1986. In: The Book of Music and Nature: An Anthology of Sounds, Words, Thoughts, (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 37.

[6] Hsiao, Cathy. Title card from documentation of Density (2016-17). http://www.plantandanimalstudio.info/sound/

[7] Cage, John, “The Future of Music: Credo,” Originally published in 1937. In: Silence: lectures and writings, (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961).

[8] Hsiao, Cathy. Title card from documentation of Squeezing Sorrow From an Orange (2016). http://www.plantandanimalstudio.info/sound/

[9] Ibid.

[10] Email from the artist, Cathy Hsiao, 2017

[11] Hsiao, Cathy. Title card from documentation of Program for Plants (2016). http://www.plantandanimalstudio.info/sound/

[12] Email from the artist, Cathy Hsiao, 2017

[13] Gordon, Lydia, “Interview with MFA Artist Cathy Hsiao”, 2016. http://sites.saic.edu/mfa2016/interview-with-mfa-artist-cathy-hsiao/